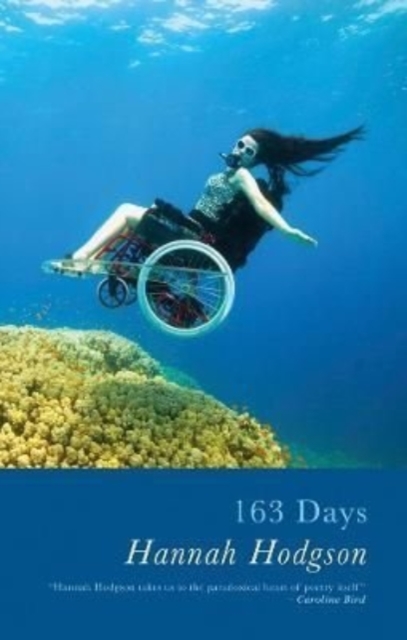

163 Days

Hodgson, Hannah More by this author...£9.99Out of stock

Please contact the shop to check availability

- Poetry

- Disability

- Disabled Writers

Hannah Hodgson is a seriously ill poet, who uses a panoply of vocabularies to evoke the medical, the poetic and professional to explore what illness, death and dying does to a young person, as both patient and witness . 163 Days is the longest hospitalisation she has had to date – and so, with this as a scaffold she charts how medical, legal and personal truths clash as loudly as a dropped tray of instruments in a silent operating theatre.

In this long singular poem, she probes what she once thought of as truth, what the law considers the truth, and the traumatic truth, which is something only the body can hold. At the time of this narrative she is sixteen, turning seventeen in a hospital ward decked out in primary colours, clowns who volunteer to visit unwell children, and four Easter Eggs per patient on a ward where only one child can eat. That child is stared at while they eat, as Hannah begins to forget the taste of food.

Doctors struggle to diagnose her overlapping chronic health conditions which began with rapid weight loss and means she cannot eat or absorb nutrients properly. She suffers heart-rending symptoms as well as all numerous, often very painful, tests and procedures that are necessary to keep her alive long enough to figure out what is wrong with her. Each day features two entries, a diary-like poem exploring her version of the day, and another charting notes that could be found within medical notes.

The diary-like entries by the author are distinguished by both clarity and despair. She has a gift for description that brings us, sometimes almost unbearably close, to her suffering.

We feel her sorrow but also her frustration at being undiagnosed, yet subject to hospital routines that sometimes seem arbitrary, like the need to sweep up and dispose of the cards from her friends, deemed an ‘infection risk’. Likewise, hospital staff seem sometimes wonderfully kind and at others, seemingly casually negligent, cold or cruel. The length of time means she goes through numerous shifts, staff rotas and medical student rotations.

The institutional quality of the institution is at question here, as is the freedom of the vulnerable individual in this setting. At one point, at 17, she is ‘too old’ for the children’s hospital yet ‘too young’ for the adult ward. The lobbying involved in solving this dilemma is both impressive and absurd; there are meetings held between adults and children’s hospitals about care responsibilities, meetings she wasn’t allowed to attend.

Beyond the ethics and machinery of care, what the diary entries show most movingly is the author’s coming-of-age story, learning both kind and terrible truths which it takes healthy adults a lifetime to amass.

In the ‘aftercare’ poems we see the author embark on a new version of her life as a disabled young person, a hospice user, a body disintegrating, declining to the extent she has seventeen (diagnosed) issues, falling under the branch of her life limiting diagnosis. Readers will be moved, surprised and enlightened by this compelling debut collection of poems.